Channels

Special Offers & Promotions

Scientists Succeed in Growing Human Brain Tissue in "Test Tubes"

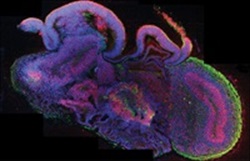

Complex human brain tissue has been successfully developed in a three-dimensional culture system established in an Austrian laboratory.

The method described in the current issue of NATURE allows pluripotent stem cells to develop into cerebral organoids - or "mini brains" - that consist of several discrete brain regions. Instead of using so-called patterning growth factors to achieve this, scientists at the renowned Institute of Molecular Biotechnology (IMBA) of the Austrian Academy of Sciences (OeAW) fine-tuned growth conditions and provided a conducive environment. As a result, intrinsic cues from the stem cells guided the development towards different interdependent brain tissues. Using the "mini brains", the scientists were also able to model the development of a human neuronal disorder and identify its origin - opening up routes to long hoped-for model systems of the human brain.

The method described in the current issue of NATURE allows pluripotent stem cells to develop into cerebral organoids - or "mini brains" - that consist of several discrete brain regions. Instead of using so-called patterning growth factors to achieve this, scientists at the renowned Institute of Molecular Biotechnology (IMBA) of the Austrian Academy of Sciences (OeAW) fine-tuned growth conditions and provided a conducive environment. As a result, intrinsic cues from the stem cells guided the development towards different interdependent brain tissues. Using the "mini brains", the scientists were also able to model the development of a human neuronal disorder and identify its origin - opening up routes to long hoped-for model systems of the human brain.

The development of the human brain remains one of the greatest mysteries in biology. Derived from a simple tissue, it develops into the most complex natural structure known to man. Studies of the human brain's development and associated human disorders are extremely difficult, as no scientist has thus far successfully established a three-dimensional culture model of the developing brain as a whole. Now, a research group lead by Dr. Jürgen Knoblich at the Institute of Molecular Biotechnology of the Austrian Academy of Sciences (IMBA) has changed just that.

BRAIN SIZE MATTERS

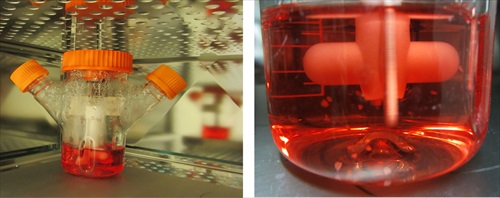

Starting with established human embryonic stem cell lines and induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, the group identified growth conditions that aided the differentiation of the stem cells into several brain tissues. While using media for neuronal induction and differentiation, the group was able to avoid the use of patterning growth factor conditions, which are usually applied in order to generate specific cell identities from stem cells. Dr. Knoblich explains the new method: "We modified an established approach to generate so-called neuroectoderm, a cell layer from which the nervous system derives. Fragments of this tissue were then maintained in a 3D-culture and embedded in droplets of a specific gel that provided a scaffold for complex tissue growth. In order to enhance nutrient absorption, we later transferred the gel droplets to a spinning bioreactor. Within three to four weeks defined brain regions were formed."

Starting with established human embryonic stem cell lines and induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, the group identified growth conditions that aided the differentiation of the stem cells into several brain tissues. While using media for neuronal induction and differentiation, the group was able to avoid the use of patterning growth factor conditions, which are usually applied in order to generate specific cell identities from stem cells. Dr. Knoblich explains the new method: "We modified an established approach to generate so-called neuroectoderm, a cell layer from which the nervous system derives. Fragments of this tissue were then maintained in a 3D-culture and embedded in droplets of a specific gel that provided a scaffold for complex tissue growth. In order to enhance nutrient absorption, we later transferred the gel droplets to a spinning bioreactor. Within three to four weeks defined brain regions were formed."

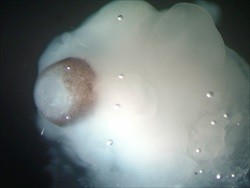

Already after 15 - 20 days, so-called "cerebral organoids" formed which consisted of continuous tissue (neuroepithelia) surrounding a fluid-filled cavity that was reminiscent of a cerebral ventricle. After 20 - 30 days, defined brain regions, including a cerebral cortex, retina, meninges as well as choroid plexus, developed. After two months, the mini brains reached a maximum size, but they could survive indefinitely (currently up to 10 months) in the spinning bioreactor. Further growth, however, was not achieved, most likely due to the lack of a circulation system and hence a lack of nutrients and oxygen at the core of the mini brains.

MICROCEPHALY IN MINI BRAINS

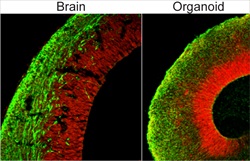

The new method also offers great potential for establishing model systems for human brain disorders. Such models are urgently needed, as the commonly used animal models are of considerably lower complexity, and often do not adequately recapitulate the human disease. Knoblich's group has now demonstrated that the mini brains offer great potential as a human model system by analysing the onset of microcephaly, a human genetic disorder in which brain size is significantly reduced. By generating iPS cells from skin tissue of a microcephaly patient, the scientists were able to grow mini brains affected by this disorder. As expected, the patient derived organoids grew to a lesser size. Further analysis led to a surprising finding: while the neuroepithilial tissue was smaller than in mini brains unaffected by the disorder, increased neuronal outgrowth could be observed. This lead to the hypothesis that, during brain development of patients with microcephaly, the neural differentiation happens prematurely at the expense of stem and progenitor cells which would otherwise contribute to a more pronounced growth in brain size. Further experiments also revealed that a change in the direction in which the stem cells divide might be causal for the disorder.

The new method also offers great potential for establishing model systems for human brain disorders. Such models are urgently needed, as the commonly used animal models are of considerably lower complexity, and often do not adequately recapitulate the human disease. Knoblich's group has now demonstrated that the mini brains offer great potential as a human model system by analysing the onset of microcephaly, a human genetic disorder in which brain size is significantly reduced. By generating iPS cells from skin tissue of a microcephaly patient, the scientists were able to grow mini brains affected by this disorder. As expected, the patient derived organoids grew to a lesser size. Further analysis led to a surprising finding: while the neuroepithilial tissue was smaller than in mini brains unaffected by the disorder, increased neuronal outgrowth could be observed. This lead to the hypothesis that, during brain development of patients with microcephaly, the neural differentiation happens prematurely at the expense of stem and progenitor cells which would otherwise contribute to a more pronounced growth in brain size. Further experiments also revealed that a change in the direction in which the stem cells divide might be causal for the disorder.

"In addition to the potential for new insights into the development of human brain disorders, mini brains will also be of great interest to the pharmaceutical and chemical industry," explains Dr. Madeline A. Lancaster, team member and first author of the publication. "They allow for the testing of therapies against brain defects and other neuronal disorders. Furthermore, they will enable the analysis of the effects that specific chemicals have on brain development."

Original publication: M. A. Lancaster, M. Renner, C.-A. Martin, D. Wenzel, L. S. Bicknell, M. E. Hurles, T. Homfray, J. S. Penninger, A. P. Jackson & J. A. Knoblich. Cerebral organoids model human brain development and microcephaly. Nature, doi: 10.1038/nature12517

About Jürgen Knoblich:

About Jürgen Knoblich:

Jürgen Knoblich started his scientific career as a graduate student at the Max Planck Institute in Tübingen. After his PhD Jürgen Knoblich joined the laboratory of Drs. Yuh Nung in San Francisco as post doctoral fellow. In 1997 Jürgen Knoblich became a group leader at the Institute of Molecular Pathology (IMP) in Vienna, Austria. In 2004 he became a senior scientist at the Institute of Molecular Biotechnology of the Austrian Academy of Sciences (IMBA) and he was appointed deputy scientific director in 2005.

About Madeline A. Lancaster:

About Madeline A. Lancaster:

Madeline A. Lancaster received her PhD from the University of California, San Diego in 2009 where she worked in the laboratory of Professor Joseph Gleeson as a NIH Genetics Training grant fellow and ARCS scholar studying signaling in cilia during development and homeostasis. In 2010, she joined the laboratory of Jürgen Knoblich at IMBA, where she was awarded an EMBO postdoctoral fellowship and then a HHWF fellowship. She is currently a Marie Curie postdoctoral fellow working on differentiation of stem cells along the neural lineage.

The Institute of Molecular Biotechnology (IMBA) combines fundamental and applied research in the field of biomedicine. Interdisciplinary research groups address functional genetic questions, particularly those related to the origin of disease. IMBA is a subsidiary of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, the leading organization promoting non-university academic basic research in Austria. Earlier this year IMBA was voted as second to top international workplace for postdoctoral researchers, by readers of the US based and online life sciences magazine, The Scientist.

About the Austrian Academy of Sciences (ÖAW)

The Austrian Academy of Sciences is the largest non-University research organisation in Austria. Within the Austrian Academy of Sciences, renowned researchers from 28 research institutions have formed a comprehensive knowledge pool covering a wide array of disciplines for the sake of progress in science as a whole. All of the Academy's activities are closely networked at national, EU, and international level with university and non-university partners.

For more information contact Jürgen Knoblich,Institute of Molecular Biotechnology of the Austrian Academy of Sciences (IMBA) Dr. Bohr-Gasse 3,1030 Vienna, Austria, tel +43 / 1 / 790 44 - 4800

Media Partners